You can generally sue a company for food poisoning if the following applies:

- You were diagnosed with food poisoning and testing was conducted to determine the pathogen that made you sick

- Your illness can be linked to a food product sold by a restaurant, grocery store, and/or food company.

If you were sickened in an outbreak of illnesses, it is important that your case be laboratory-confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or your state health department.

Were You Sickened by E. coli, Listeria, Salmonella, or another Pathogen?

To be part of an outbreak, testing will need to be done to find out what pathogen made you sick before you can sue for food poisoning:

- Botulism (caused by Clostridium botulinum)

- Campylobacter

- Cyclospora

- E. coli

- Hepatitis A

- Listeria Monocytogenes

- Norovirus

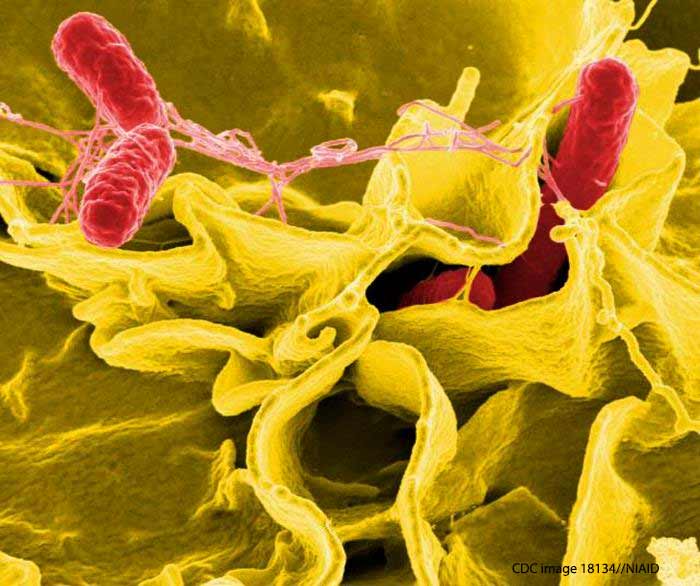

- Salmonella

- Shigella

- Vibrio.

All of these pathogens are bacteria except Hepatitis A and Norovirus, which are viruses.

How Can You Link My Case of Food Poisoning to a Company?

If your illness is bacterial, genetic testing will need to be conducted to get a DNA “fingerprint” of the bacteria. This is generally done with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and/or whole-genome sequencing (WGS). These fingerprints, actually genetic patterns, are used as evidence in a lawsuit against a corporation that sold contaminated food.

We are a national food poisoning litigation law firm, and we have used PFGE and WGS evidence to win millions for victims of food poisoning, including a settlement for over $6 million and a $7.5 million verdict.

Our lawyers help people like you sue for food poisoning and win personal injury and wrongful death lawsuits. We have helped people in almost every state in the United States. We are not paid unless you win.

How Can Our Lawyers Help You?

Contact our law firm to request a free consultation with a lawyer.

Proving a Case

Under the law, a person injured by food poisoning has to prove three things in order to make a successful strict liability claim in a food poisoning case:

- The Food was Contaminated with a Foodborne Pathogen – There has to be some evidence that the food was contaminated with a pathogen. This can be done with microbiological evidence (e.g. E. coli, Listeria, Salmonella, or another pathogen is found in a sample of the food) and/or epidemiological evidence (e.g. dozens of people who ate at the same restaurant around the same time contracted E. coli infections). Read “What is the incubation period for E. coli, Listeria, Salmonella and Other Pathogens?“

- Causation – The contaminated food actually caused the food poisoning victim’s illness.

- Damages – As a result of the food poisoning, the person was harmed physically, mentally, and financially.

This involves a number of disciplines including medicine, microbiology, epidemiology, sanitation, food safety, and agriculture, among others. But ultimately, all of the facts deduced from these disciplines have to be judged according to the law in the state in which the injury occurred. Simply put, what is that law, and what does it require (and, equally important, not require)?

Food safety lawyers merge science and law to win food poisoning cases.

What Does the Law Require to Win a Food Poisoning Lawsuit?

A recent California case answers this question.

In Sarti v. Salt Creek Ltd., a young woman became very ill as a result of an infection involving a type of bacteria, Campylobacter, that’s often found on raw chicken. She claimed it came from the food she ate at the Salt Creek Grille.

She did not eat chicken at the restaurant. Rather, she ate an appetizer consisting of raw ahi tuna, avocado, cucumber, and soy sauce. None of those ingredients are thought to typically harbor Campylobacter. Those ingredients can, however, carry the bacteria if they come in contact with (cross-contamination) raw chicken or the utensils used to prepare it.

After the woman became ill and a report was made to the health department, the restaurant was inspected and a number of improper sanitation issues were identified that could lead to campylobacter cross-contamination. However, as is often the case in such investigations, there was no “smoking gun” conclusively establishing that the improper food practices actually caused the food she ate to be contaminated.

The doctor who treated the young woman testified that it was more likely than not that the restaurant’s improper practices caused her Campylobacter infection. The jury agreed and awarded her substantial money damages. An appeal followed in which the issue was whether there was enough evidence to support the verdict.

On appeal, the restaurant contended that unless the young woman could rule out every other possible cause of her illness, she could not win. In other words, she would have the burden of proving that absolutely no other food, surface, or person caused her illness. The appeals court called this position “untenable” and concluded:

At this point, we should confront the semantic danger in the word “possibility.” The word must necessarily connote something more than bare conceivability or plausibility, otherwise it would swallow up the universe. For example, in a food poisoning case, how could the plaintiff disprove that she didn’t pick up some nasty bacteria (here, Campylobacter) because she touched a doorknob that had been previously touched by someone who had been handling raw chicken or who had changed a diaper, and hadn’t washed his or her hands? Well, yes, one might reason, it is conceivable that that might have happened. It is ludicrous, though, to suggest that such bare conceivability must, as a matter of law, defeat a food poisoning claim.

Instead, the court determined that the woman had met her burden of proof by offering expert testimony that linked the Campylobacter and the particular unsanitary conditions found at the restaurant. In other words, it was all right for the jury to infer that linkage without requiring the woman to disprove every other potential source, no matter how remote.

This decision makes good common sense. If the restaurant’s position had been accepted, it would be virtually impossible to win a foodborne illness case. Victims would have to exclude every other cause or source, which is a physical and intellectual impossibility. Fortunately, the California court didn’t see it that way.

If you have questions or concerns, read a message from Pritzker Hageman founder Fred Pritzker about food safety lawsuits.

More Information

- Food Recall

- PFGE

- Food Safety

- Food Poisoning Attorney

- Beef Recall

- Can I Sue Kroger for Food Poisoning?

- Cheeseburger Recall

- Chili Recall

- Sprouts Recall

- 5 Characteristics of a Good Food Safety Lawyer

- Anaphylactic Shock Lawyer

- Bad Bug Law Team

- Clostridium Perfringens

- How a Food Lawyer Proves a Food Poisoning Claim

- Olive Garden Lawsuit

- Raw Milk

- Reactive Arthritis

- School Food Poisoning

- Should I Go to the Doctor if I Suspect Food Poisoning?

- What is Cryptosporidium?

- What is Cyclosporiasis?

- When Your Pet is Injured

- Diabetes and Food Poisoning