Last July, a 10-month Salmonella outbreak linked to ground beef ended after sickening 106 people, killing one of them. Despite its size and severity, no warnings or consumer advisories were issued about the outbreak as it spread through 21 states, hospitalizing about half of the case-patients who ranged in age from 1 to 88. In fact, health officials made no mention of the outbreak until a report about it appeared in a CDC journal last month- 10 months after the deadly outbreak ended.

Our team of experienced Salmonella attorneys has one question, why?

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA FSIS), the federal agency charged with protecting public health by ensuring the safety of meat, poultry, and processed egg products, the answer is that there was “no actionable information.”

So, what information was gathered in the months-long investigation of this outbreak? First, a word about ground beef production.

Although most ground beef produced in the U.S. comes from beef cattle, 18 percent comes from retired dairy cows and dairy cows have a known, longstanding problem with Salmonella Newport. “Previous studies have demonstrated long-term persistence of Salmonella Newport in dairy herds and a 1987 Salmonella Newport outbreak was linked to contaminated ground beef from slaughtered dairy cows,” the CDC states in its report. When milk production of dairy cows becomes insufficient, they are sold either directly to slaughterhouses or through sale barns.

Ground Beef Salmonella Outbreak Investigation

Health officials used whole-genome sequencing to determine that the Salmonella Newport strain cultured from 106 patients, leftover ground beef from one of the patients’ homes and four dairy cows from New Mexico all likely shared a common source. Sixty percent of the patients interviewed bought ground beef at one of two national grocery store chains.

FSIS was able to identify the farm where one of the cows came from and the Texas slaughterhouse where it was killed. Health officials visited this farm but did not collect samples for testing. The agency cited “confidentiality practices” as the reason it could not identify the farm or farms of origin for the three other dairy cows and pointed out that the ground beef that tested positive for the outbreak strain was not produced at the Texas slaughterhouse.

Because FSIS could not identify a common production lot of ground beef, narrow the investigation to a single slaughterhouse where the ground beef was processed, or find the outbreak strain in ground beef in its original packaging taken from a patient’s home, the agency did not request a recall or issue a public warning. FSIS made a similar argument during the Foster Farms Salmonella outbreak that began in 2013 and ended in 2014.

Foster Farms Salmonella Outbreak

Poultry producer Foster Farms was linked to a 29-state Salmonella Heidelberg outbreak that sickened 634 people between March 2013 and July 2014. Among those who became ill was 18-month-old Noah Craten whose Salmonella infection created abscesses in his brain. To save his life, surgeons had to cut open Noah’s skull and remove the abscesses.

Noah’s story was featured in a Frontline report, The Trouble with Chicken, which examined the decade-long Salmonella problem at Foster Farms, spotlighted the USDA’s lack of enforcement ability and asked the question who is accountable when food makes people sick? All three of these issues were addressed in the landmark Salmonella lawsuit Pritzker Hageman filed on behalf of the Craten family.

In July 2013, Foster Farms was made aware that its product was under investigation but only initiated a, very limited, recall of its tainted chicken on July 12, 2014. Despite months of outbreak updates from the CDC stating “epidemiologic, laboratory, and traceback investigations conducted by local, state, and federal officials indicate that consumption of Foster Farms brand chicken is the likely source of this outbreak of Salmonella Heidelberg infections,” FSIS seemed to drag its heels.

“Until this point, there had been no direct evidence that linked the illnesses associated with this outbreak to a specific product or production lot,” the agency said at the time of the recall. Evidence required for a recall, FSIS said, included “case-patient product that tests positive for the same particular strain of Salmonella that caused the illness, packaging on product that clearly links the product to a specific facility and a specific production date, and records documenting the shipment and distribution of the product from purchase point of the case-patient to the originating facility.”

The ground beef outbreak is an example of what happens when necessary records are nonexistent. “For this outbreak, tracing back cows at slaughter/processing establishments to the farm from which they originated was problematic because cows were not systematically tracked from farm to slaughter/processing establishments,” the report states.

Ground Beef Salmonella Outbreak

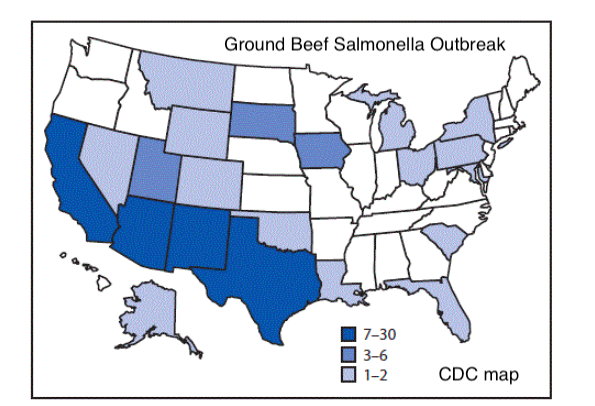

In January 2017, health officials identified a cluster of illnesses caused by the same strain of Salmonella Newport. Eventually, they would learn that between October 4, 2016, and July 19, 2017, 106 people in 21 states were part of the outbreak. Cases were reported from: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming. Most of them were concentrated in southwestern states with Arizona reporting 30, California reporting 25, New Mexico reporting 14 and Texas reporting seven.

Health officials interviewed 65 case-patients and identified ground beef as a common exposure. Eighty percent of those interviewed (52 patients) said they ate ground beef at home in the week before illness began. Of those, 31 patients reported buying the beef from multiple locations of two national grocery chains. The other 21 reported buying ground beef from locations of 15 other grocery chains.

Some of the case-patients recalled how the ground beef they purchased was packaged, according to the report. Fifteen of them said they purchased ground beef in rolls or tubes called “chubs” ranging in size from 2 lbs. to 10 lbs. Eighteen said they purchased it on plastic-wrapped trays and two said the ground beef they bought was in pre-formed hamburger patties. Twenty-nine people said they bought fresh ground beef, four said they bought frozen ground beef. Others could not remember.

To conduct its “traceback” investigation, FSIS user shopper card records or receipts from 11 patients to try and identify the origin of the ground beef. (The report does not state how many grocery store chains were associated with these 11 purchases.) This effort uncovered 10 companies with about 20 different beef suppliers. According to the report, “10 of the 11 records traced back to five company A slaughter/processing establishments, seven of 11 traced back to five company B slaughter/processing establishments, and four of 11 traced back to two company C slaughter/processing establishments.”

Health officials tested opened, leftover samples of ground beef the collected from three patients’ homes. All three of the packages collected for testing were purchased from one of two national grocery chains that had been identified by a majority of patients. “One sample of ground beef collected from a patient’s home, that had been removed from its original packaging, yielded the outbreak strain. The other two samples did not yield Salmonella,” according to the report.

What Does This Mean for Consumers?

Whole-genome sequencing tests showed that samples cultured from the 106 patients, the four dairy cows and the leftover ground beef were all closely related, suggesting they all shared a common source, but traceback investigations pointed to multiple lots and slaughterhouses. One reason may be that dairy cows carrying a high Salmonella load that overwhelmed antimicrobial interventions could have gone to multiple slaughter/processing establishments, resulting in contamination of multiple brands and lots of ground beef,” the report states.

If you believe you were part of this outbreak and would like a free consultation with a Salmonella attorney at Pritzker Hageman, call 1(888)377-8900 (toll-free) or use this contact form. There is no obligation.